The Text

Last Time on ‘The Story’

Last time when we left our heroes, Israel (aka Jacob) and his family all ended up in the land of Egypt. Jacob and Joseph both die, and the Genesis scroll ends with a list of the brothers. The Scroll of Exodus (which means the ‘coming out of’) begins some four hundred years later with a list of those same sons, who have now become the tribes of a fledgling nation. However, a new Pharaoh (King of Egypt) arises who does not remember Joseph and all that he did for Egypt, and sees that there is a large number of foreigners in his land. These people carry the blessing of Abraham and have multiplied greatly, so much so that the Pharaoh fears that they will rise up against Egypt. Pharaoh then begins a multi-step campaign against the people, first enslaving them and using their labor to build up Egypt. The people continue to multiply despite hard labor, so Pharaoh attempts to thin the herd, first by enlisting midwives to kill the male babies (which they do not do because they fear the LORD), and then an edict proclaiming that all Hebrew baby boys must be thrown into the Nile river. One woman, from the tribe of Levi, gets by on a technicality when she puts her son into a basket and floats him down the Nile, where he is discovered by Pharaoh’s daughter and adopted. Pharaoh’s daughter names the baby Moses (in Hebrew Moses sounds like ‘drawn out’, in Egyptian it sounds like ‘son’). Moses grows up in Pharaoh’s house, but one day he kills an Egyptian guard for mistreating a Hebrew, and flees to Midian. Moses settles into life in Midian and is there for forty years. While watching his father-in-law’s flock, God speaks to him from a burning bush, and tells him to go back to Egypt to free his people. Eventually he agrees, and along with his brother Aaron, tries to convince Pharaoh to let the people go. Pharaoh’s initial reaction is to give the Hebrews more work since they have all this free time to think about freedom. The Hebrews are not big fans of this, and confront Moses and Aaron who assure them that God has sent them and that they will all be free. Through Moses and Aaron, God sends plagues (strikes) against Egypt, first effecting the whole land, and then specifically exempting the Hebrews. Pharaoh’s heart continues to be hard (more about that later), and refuses to let them go until the tenth plague when all firstborns in the land, except those whose houses are marked with the blood of the Passover Lamb, are killed. Pharaoh finally relents, and Moses leads the Hebrews out of Egypt, and they are camping by the sea.

Today’s Story

Today’s story is a dramatic one, great for the big screen, and so, many are familiar with it. However, there are certainly some interesting things that can keep the telling of this story fresh.

Pharaoh’s Heart: We are told multiple times in this story, and in one of the skipped verses of this pericope, that “God hardened Pharaoh’s heart.” This is a strange phrase, and makes it seem as if God is purposefully bringing about this outcome. Now, this is traditionally the interpretation that God’s purpose in this Exodus is not only the freeing of this people, but showing the LORD’s divine power over and above the gods of Egypt. Exodus 6:1-8 gives God’s manifesto for this project, to show God’s power, not only to the Egyptians, but to the Hebrews. Interestingly enough, this translation of hardening Pharaoh’s heart may not be quite right, and could be translated more like ‘weigh his heart’. Egyptian mythology includes the concept of an afterlife in the Field of Reeds. To enter into the Field of Reeds, an Egyptian is judged after death by Osirus, and their heart is weighed to see if it is lighter than a feather. Some suggest that in the text God is not so much ‘hardening’ Pharaoh's heart, but weighing it in the Egyptian sense (for more information, see Marvel’s Moon Knight).

We have all seen or been in the situation of being committed to a particular course of action. As we get further down the line, it gets harder and harder to choose a different course. Throughout the story we see Pharaoh commit to a course of action that is clearly self-destructive. Even his own people plead with him to give in (Exodus 10:7), but he will not relent. It is as if his ego will not allow him to admit that his first reaction was incorrect. Even here, at the beginning of this story, Pharaoh and his officials realize the implications of their decision to let the Hebrews go. Their economy has been shaped around a large and cheap labor force, and it will not be easy to change (For more information see: Reconstruction, Jim Crow, Civil Rights, Black Lives Matter). So they decide to do something about it.

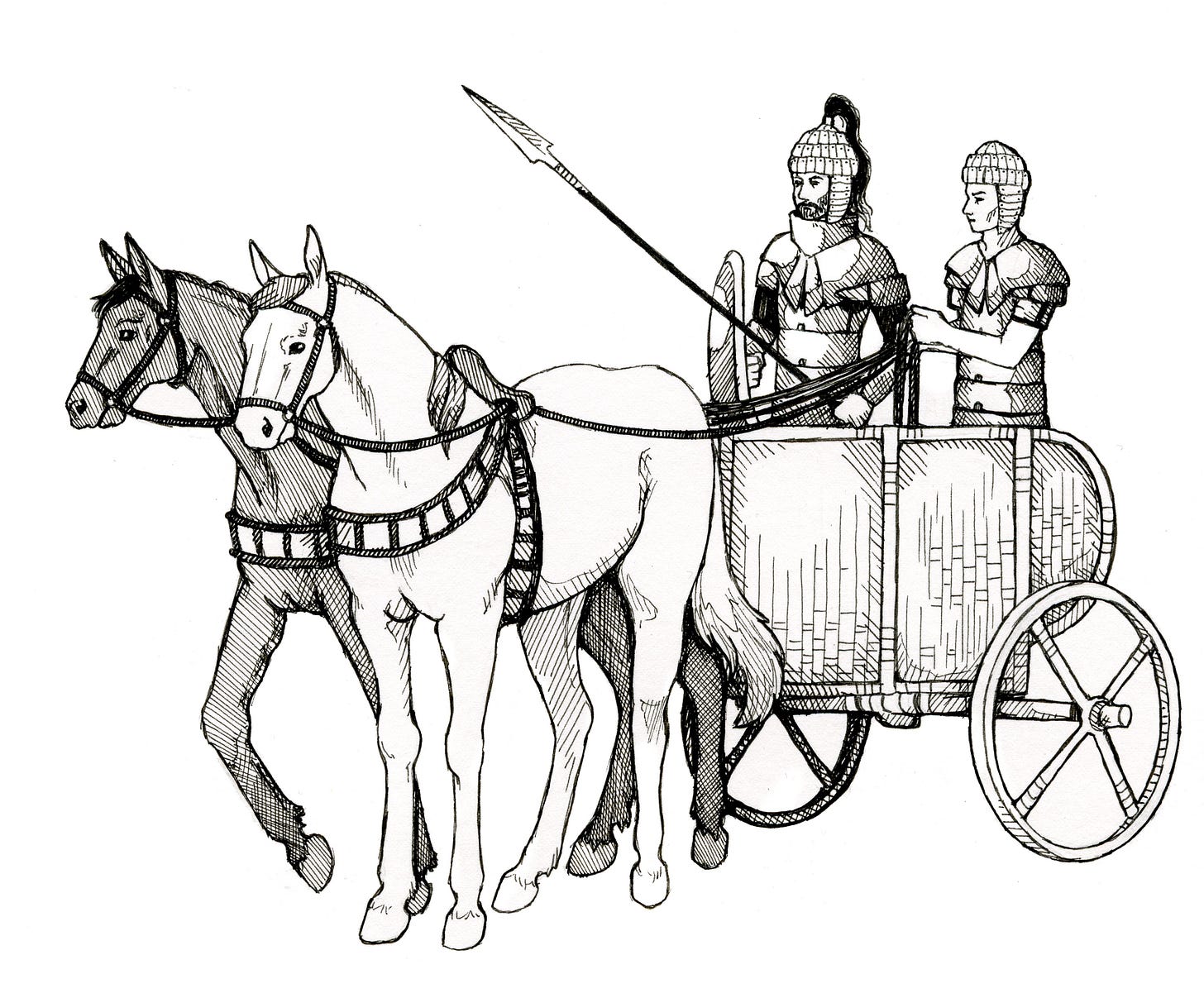

Chariots: Outside of the ancient world, it is difficult to understand the significance of chariots. As far as military might goes, they were like Patriot Missiles or a tank. They were wheeled carts pulled by one or two horses. Each chariot had a pilot and one or two warriors who would wield arrows, javelins, spears, and/or swords, depending on range to the enemy. Each chariot team of pilots and warriors would likely train together so they would operate as one cohesive unit, and train with other chariot teams in order to operate effectively together. These machines were mobile weapons platforms which could easily overcome an enemy on foot. The six hundred ‘picked’ chariots were historically covered with a brasslike mettle so that they shone in the sun. In addition, we are told that “all the other chariots of Egypt” were with them as well. Now, this is most likely a hyperbolic telling, but it certainly conjures a sense of overwhelming military force, especially against a mostly civilian population. With our prophetic imagination, we can picture how it would look: the dust kicked up by the horses rising above the horizon, the glints of light coming off of the chariots, armor, and weapons of the Egyptian army. We can imagine the growing intensity of the ground shaking as a thousand plus horses gallop towards the camp. You can smell the dust, and the palpable fear as the recently ex-slaves around you become increasingly aware of how truly well and deeply screwed you all are. This is the picture that is intended. Even if the Hebrews are able to mount a military defense, there is no way that they will be able to stand against the Egyptian army’s military might. So we go on to the other option.

The Sea: The Hebrews are camping ‘by the sea’ according to the previous verses. So, there is some disagreement on what sea exactly they are bordering. The ‘traditional’ (Modern Western) interpretation is that they are on the shore of the “red sea,” the body of water between ancient (and modern) Egypt and the Sinai Peninsula. It is a seawater inlet of the Indian Ocean and the northernmost tropical sea. It has an average depth of 490 meters/ 1,600 feet, but also has several shallow shelves. However, the Hebrew itself calls it the ‘Reed Sea’ which suggests we might be talking about something more like a swamp/estuary situation. Side note: I am not sure of the significance, but I wonder if there is a connection to the ‘field of reeds,’ the Egyptian afterlife. Whether it is a large body of water or a smaller one, the sea does not provide a viable retreat for the people, and so they begin to panic and complain (a common refrain through the Exodus scroll).

Complaint: I may not have to tell you that this is a common reaction of groups in stressful situations. Whether they are staring down an Egyptian army or believe that they are not singing enough of the hymns they know, groups of people start to complain to leaders quickly. If we are really honest, this is also our favorite reaction in high stress situations as well. We complain to our peers, our loved ones, and the internet.

This particular complaint comes with high level of sass as well, asking a rhetorical question about the number of graves in Egypt. Get used to this response, because this group will do it a lot through the rest of the story, every time they get into a tough situation, they will complain to Moses/God. It seems like matter how many times God will provide for them, they still go right into complaining (much like us). Complaint often betrays our lack of scope on a situation. This group see only two possible outcomes, face an army or retreat across the water, and neither of them are good. When we complain we also are usually signaling that the small set of desired outcomes that we would prefer are not available to us, and that we lack the imagination to see outside of the circumstances in front of us.

God’s Solution: The solution that the LORD provides is by no means the expected one. God instructs Moses to raise his staff over the waters. There is an explanation of winds driving the water, and the Hebrews are able to go across the water on dry land. The mud, however, turns the Egyptian advantage into a liability, and the chariot wheels get stuck long enough to let the Hebrews go across, and the waters to fill back in, drowning the Egyptians.

How often are we blind to the things that God is doing through our challenges, the unexpected paths that God provides, the unexpected victories we are provided with? For me, this sermon comes at the beginning of our church’s Stewardship Campaign. The idea of both a deeply challenging situation, and that God can provide a way that we do not see, will definitely preach. Perhaps it can for you as well.

Violence: Of course, we also should at least be aware of the overall issues of violence, especially in the Hebrew Scriptures. It is troubling, especially for modern readers to hear a divine solution which necessitates the destruction of Pharaoh and his army, which are also human beings bearing the image of God. Here are some of my thoughts:

First of all, we must acknowledge the literary role and intent of the destruction of the Egyptian army. This is the final strike against not only Egypt but against the gods of Egypt. In the ancient world, battles were almost always seen as playing out divine contests. They were one way to know whose god was more powerful. This story takes that motif an expresses it to an almost ridiculous level, not only does YHWH have victory over the Egyptian gods, but the Hebrews don’t even fight in order for this victory to be accomplished. The Natural world itself deals the final blow against Pharaoh and his army. As such, the loss of life may be over exaggerated or even fictitious in order to tell an important story about the salvific power of the Lord of Hosts. In this case, the Egyptian army fulfills the same function of any ‘evil army.’ No one cries over the destruction of those on the Death Star, because they are a) faceless (sometimes literally) bad guys, and b) they had already destroyed multiple civilian populations with this weapon, and were poised to do the same again.

If we take the story as being more literally true, we also need to take the rest of the narrative account into mind, especially Pharaoh’s dogged pursuit. Over and over, the narrative is clear that Pharaoh sets himself against God. He has learned this lesson over and over, with increasing severity through the ten plagues/strikes. As mentioned above, his own advisors suggest that he let the people go instead of continuing to experience disaster after disaster. Therefore, while God does drown this army in the sea, they also had been ordered into that position by Pharaoh. This puts their death more in the realm of a Disney Villain, who is ultimately killed as a result of their own actions, rather than those of the hero.

At the end of the day, however, we need to struggle with these types of texts. Theodicy, the general term for solutions to the ‘why does God allow bad things to happen’ question is a really big field of theology with a lot of possible answers. There are a whole menu of answers from which we can choose in responding; from God’s divine providence willing the death of thousands of Egyptians for some greater good which is ultimately beyond our comprehension, to a God in Process who is either unable or unwilling to effect the natural order in order to stop these deaths, and everywhere in-between.

The Rest of the Story

We actually don't have a lot of the story between this week and next week’s reading. Immediately after the crossing of the Red/Reed Sea, Miriam, Moses’s sister, sings a song of praise to God, which Moses immediately poaches and gets the writing credits for. The people will make their way through the wilderness of sin (which, by the way, is not ‘sin’ like falling short of the glory of God, but with a long ‘i’ as in the first part of Sinai). They run out of water, complain, and God gives them water. They run out of food, complain, and God provides food (manna, which literally means ‘what is it?’ This could easily be integrated into World Communion Sunday liturgy). They get attacked by the Amalikites (which earns this particular tribe long-standing ire (side note, the Amalikites are also pretty hated in the Koran as well)). Right before they get to Mt. Sinai, Jethro, Moses’ father in law catches up with them, and gives some wisdom. Then they get to Mt. Sanai which leads us up to next week’s lesson.

Pop Culture References

So the most obvious ones here are cinematic retellings of the Exodus story. The Ten Commandments has one of the most iconic scenes in cinema history.

<iframe width="876" height="438" src="

title="Moses parted the Red Sea" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

I am a big fan of the version from Prince of Egypt too.

<iframe width="853" height="480" src="

title="The Prince of Egypt (1998) - Parting the Red Sea Scene (9/10) | Movieclips" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

I mentioned it before, but the Battle of Yavin from Star Wars is a pretty good illustration. The whole battle is based not on a direct military assault, but taking advantage of a small design flaw (in other words, victory in a non-obvious way). Victory is also obtained through a mystical/spiritual force.

<iframe width="853" height="480" src="

title="Star Wars: A New Hope | Luke Destroys The Death Star | 4K HDR" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

Hymn Suggestions

Guide Me Oh Thou Great Jehovah (GTG 65, PH 281)

Your Endless Love Your Mighty Acts (GTG 60)

The Trees of the Field (GTG 80)

When Israel Was in Egypt’s Land/Go Down, Moses (GTG 52, PH 334)

Come, Ye Faithful, Raise the Strain (GTG 234, PH 114/5)

Deep in the Shadows of the Past (GTG 50)

God of the Ages, Whose Almighty Hand (GTG 331, PH 262)

Links

The Bible Binge Podcast: Moses Crosses the Red Sea (Check out the episodes before hand for more of Moses’s story)

The Bible Project: God Tests His Chosen Ones (But also check out the ones before for the rest of the story of the Exodus)

My Sermon from 2019 (I did not review, no promises)

Prayer of the Day

God of redemption, you call us to step out in faith and trust that you will be with us. Help us see beyond the answers that we are expecting, to the salvation that you are opening before us. Guard us from the fears and complaints that can obscure your calling. Amen.